Contents

- 1 Essay Answer Type Questions

- 1.1 Question 1.

- 1.2 Answer:

- 1.3 Question 2.

- 1.4 Answer:

- 1.5 Question 3.

- 1.6 Answer:

- 1.7 Question 4.

- 1.8 Answer:

- 1.9 Question 5.

- 1.10 Answer:

- 1.11 Question 6.

- 1.12 Answer:

- 1.13 Question 7.

- 1.14 Answer:

- 1.15 Question 8.

- 1.16 Answer:

- 1.17 Question 9.

- 1.18 Answer:

- 1.19 Question 10.

- 1.20 Answer:

- 1.21 Question 11.

- 1.22 Answer:

Essay Answer Type Questions

Question 1.

Write an essay on temperature as an ecological factor. (T.Q.)

Answer:

Temperature :

Temperature is a measure of the intensity of heat. The temperature on land or in water is not uniform. On land the temperature variations are more pronounced when compared to the aquatic medium, because land absorbs or loses heat much quicker than water. The temperature on land depends on seasons and the geographical area on this planet. Temperature decreases progressively when we move from the equator to the poles. Altitude also causes variations in temperature. For instance, the temperature decreases gradually as we move to the top of the mountains.

The Effects of Temperature in Lakes :

Thermal Stratification :

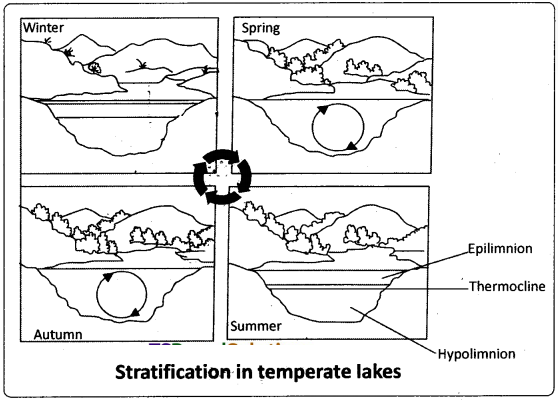

Temperature variations occur with seasonal changes in the temperature regions. These differences in the temperature form ‘thermal layers’ in water. These phenomena are called thermal stratifications.

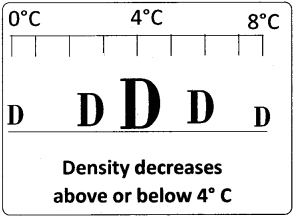

Water shows maximum density at 4°C. Rise or fall of temperatures above or below 4°C decreases its density. This anomalous property of water and the seasonal variations in temperature are responsible for the thermal stratification in temperate lakes.

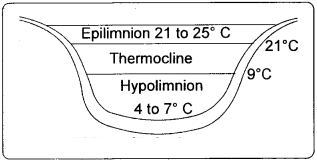

Summer stratification :

During summer in temperate lakes, the density of the surface water decreases because of increase in its temperature (21-25° C). This ‘upper more warm layer’ of a lake is called epilimnion. Below the epilimnion there is a zone in which the temperature decreases at the rate rate of 1°C per meter in depth, and it is called thermocline or metalimnion. The bottom layer is the hypolimnion, where water is relatively cool, stagnant and with low oxygen content (due to absence of photosynthetic activity).

During autumn (also called fall), the epilimnion cools down, and the surface water becomes heavy when the temperature is 4° C, and sinks to the bottom of the lake. Overturns bring about ‘uniform temperature’ in lakes during that period. This circulation during the autumn is known as the fall or autumn overturn. The upper oxygen rich water reaches the hypoliminion and the nutrient rich bottom water comes to the surface. Thus there is uniform distribution of nutrients and oxygen in the lake.

Winter stratification / stagnation :

The ‘Fall’ is followed by ‘Winter’. In this season the surface water cools down. The upper water freezes when the temperature reaches 0°C. Below the upper icy layer, the cool (4° C) water occupies the lake. The aquatic animals continue their life below the icy layer. At lower temperatures the activity of bacteria and the rate of oxygen consumption by aquatic animals decrease. Hence, organisms can survive below the frozen upper water without being subjected to ‘hypoxia’ (low oxygen availability).

In the ‘Spring season’ the temperatures start rising. When it reaches 4°C, the water becomes more dense and heavy and sinks to the bottom, taking ‘oxygen rich water’ to the bottom. The upper oxygen rich water sinks down and the bottom ‘nutrient rich water’ reaches the surface. It is called ‘spring overturn’. The lakes which show overturns twice a year are called ‘dfmictic lakes’. Thus ‘stratifications’ and ‘overturns’ help survival of organisms at all levels in deep lakes.

Biological effects of Temperature :

Temperature Tolerance :

A few organisms can tolerate and thrive in a wide range of temperatures they are called eurythermal, but, a vast majority of organisms are restricted to a narrow range of temperatures (such organisms are called stenotherma. The levels of thermal tolerance of different species determine their geographical distribution.

Temperature and Metabolism :

Temperature affects the working of enzymes and through it, the basal metabolism, and other physiological functions of organism. The temperature at which the metabolic activities occur at the climax level is called the ‘optimum temperature. The lowest temperature at which an organism can live indefinitely is called minimum effective temperature. If an animal or plant is subjected to a temperature below the minimum effective limit, it enters into a condition of inactiveness called chilLcoma. The metabolic rate increases with the rise of temperature from the minimum effective temperature to optimum temperature.

The maximum temperature at which a species can live indefinitely in an active state is called maximum effective temperature. If the temperature is raised above the maximum effective temperature, the animals enter into ‘heat coma’. The maximum temperature varies much in different animals.

van’t Hoff’s rule :

van’t Hoff, a Nobel Laureate in thermochemistry, proposed that, with the increase of every 10°C, the rate of metabolic activities doubles. This rule is referred to as the van’t Hoff’s rule, van’t Hoffs rule can also be stated in reverse saying that the reaction rate is halved with the decrease of every 10°C. The effect of temperature on the rate of a reaction is expressed in terms of temperature coefficient or Q10 value. Q10 values are estimated taking the ratio between the rate of a reaction at X°C and rate of reaction at (X – 10°C). In the ‘living systems’ the Q10 value is about 2.0. If the Q10 value is 2.0, it means, for every 10° C increase, the rate of metabolism doubles.

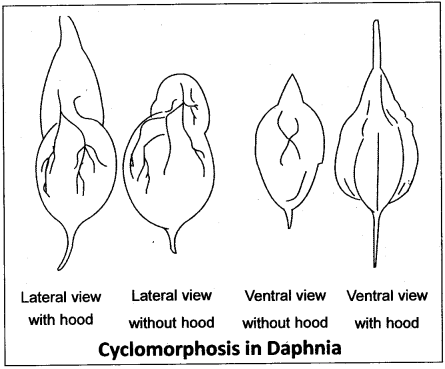

Cyclomorphosis :

The cyclic seasonal morphological variations among certain organisms is called cyclomorphosis. This phenomenon has been demonstrated in the cladoceran (a sub group of Crustacea) Daphnia (water flea). In the winter season the head of Daphnia is ’round’ in shape (typical or non-helmet morph). With the onset of the spring season, a small ‘helmet’/ ‘hood’ starts developing on it. The helmet attains the maximum size in summer. In ‘autumn’ the helmet starts receding. By the winter season, the head becomes round. Some scientists are of the opinion that cylomorphosis is a seasonal adaptation to changing densities of the water in

lakes – in summer as the water is less dense Daphnia requires a larger body surface to keep floating easily. During winter the water is more dense, and so it does not require a larger surface area of the body to keep floating. Others believe that these cyclic changes are adaptations to ‘stabilize the movement’ in water. Compared to the ’typical morphs’, the ‘helmeted morphs’ can resist the water currents better to stay in the water rich in food materials.

Temperature adaptations :

Temperature adaptations in animals can be dealt under three heads a) Behavioural adaptations, b) Morphological and Anatomical adaptations and c) Physiological adaptations.

a) Behavioural adaptations :

Some organisms show behavioural responses to cope with variations in their environment. Desert lizards manage to keep their body temperature fairly constant by behavioural means. They ‘bask’ (staying in the warmth of sunlight) in the sun and absorb heat when their body temperature drops below the comfort zone^ but move into shade when the temperature starts increasing. Some species are capable of burrowing into the soil to escape from the excessive heat above the ground level.

b) Morphological and anatomical adaptations :

In the polar seas, aquatic mammals such as the seals have a thick layer of fat (blubber) that acts as an insulatpr and reduces the loss of body heat, underneath their skin.

The animals which inhabit the colder regions have larger body size with greater mass. The body mass is useful to generate more heat. As per Bergmann’s rule mammals and other warm blooded animals living in colder regions have less surface area to body volume ratio’, than their counterparts living in the tropical regions.

The small surface area helps to conserve heat. For instance, the body size of American moose/Eurasian elk (Alces alces), increases with the latitudes in which they live. Moose of northern part of Sweden shows 15-20% more body mass than the same species (counterparts) living in the southern Sweden.

Mammals from colder climates generally have shorter earlobes and limbs (extremities of the body) to minimize heat loss. Large earlobes and long limbs increase the surface.area without changing the body volume. This is known as Allen’s rule. For instance, the polar fox, Vulpes lagopus (formerly called Alopex lagopus), has short extremities to minimize the heat loss from the body. In contrast, the desert fox, Vulpes zerda, has large earlobes and limbs to facilitate better ‘heat loss’ from the body.

c) Physiological adaptations :

In most animals, all the physiological functions proceed ‘optimally’ in a narrow temperature range (in humans, it is 37° C). But there are microbes (archaebacteria) that flourish in hot springs and in some parts of deep seas, where temperatures far exceed 100° C. Many fish thrive in Antarctic waters where the temperature is always below zero. Having realized that the abiotic conditions of many habitats may vary over a time period, we now ask – How do the organisms living in such habitats manage with stressful conditions? One would expect that during the course of millions of years of their existence, many species would have evolved a relatively constant internal (within the body) environment.

It permits all biochemical reactions and physiological functions to proceed with maximal efficiency and thus, enhance the over all’ fitness’ of the species. This constancy, could be chiefly in terms of optimal temperature and osmotic concentration of body fluids. So the organism should try to maintain the constancy of its internal environment (homeostasis) despite varying external environmental conditions that tend to upset its homeostasis. This is achieved by the processes described below.

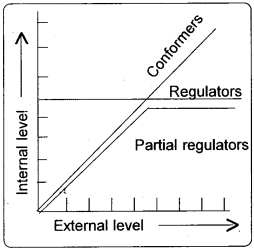

(i) Regulate :

Some organisms are able to maintain homeostasis by physiological (sometimes behavioural also ) means which ensures constant body temperature, constant osmotic concentration, etc. All birds and mammals, and a very few lower vertebrate and invertebrate species are indeed capable of such regulation (thermoregulation and osmoregulation). Evolutionary biologists believe that the ‘success’ of mammals is largely due to their ability to maintain a constant body temperature and thrive whether they live in Antarctica or in the Sahara desert.

The mechanisms used by most mammals to regulate their body temperature are similar to the one that we, the humans use. We maintain a constant body temperature of 37°C. In summer, when outside temperature is more than our body temperature, v.e sweat profusely. The resulting ‘evaporative cooling’ brings down the body temperature. In winter when the temperature is much lower than 37°C, we start to shiver (a kind of exercise which produces heat and raises the body temperature – a type of body’s own defence mechanism against low temperature). Plants, on the other hand, do rvot have such mechanisms to maintain internal temperatures.

ii) Conform :

Majority (99 percent) of animals cannot maintain a constant internal environment. Their body temperature changes with the ambient (surrounding) temperature. In aquatic animals, the osmotic concentration of the body fluids changes along with that of the surrounding water. Such animals are described as ‘conformers’.

(iii) Partially regulate :

Animals such as ‘camels’ can be ‘conformers’ up to a particular range of temperature and ‘regulator’ afterwards. So, they are described as ‘partial regulators’ or ‘partial conformers’.

Thermoregulation is energetically ‘expensive’ for many organisms. This is particularly true in small animals like shrews and humming birds. Heat loss or heat gain is a function of the surface area. Since small animals have a larger surface area relative to their volume, they tend to lose body heat very fast when it is cold outside; then they have to spend much energy to generate Body heat through metabolism. This is the main reason why very small animals are rarely found in the ‘polar regions’. During the course of evolution, the costs and benefits of maintaining a constant internal environment are taken into consideration. Some species have evolved the ability to regulate, but only over a limited range of environmental conditions, beyond which they simply conform.

If the stressful external conditions are localized or remain only for as short duration, the organism has two other alternatives.

(iv) Migrate :

The organism can move away temporarily from the ‘stressful habitat’ to a more ‘hospitable’ (comfortable) area and return when the stressful period is over. In human analogy (comparison), this strategy is comparable a person moving from Delhi to Shimla for the duration of summer. Many animals, particularly birds, during winter undertake long-distance migrations to more hospitable areas. Every winter, many places in India including the famous Keoladeo or Keoladeo Ghana National park (Formerly – Bharatpur bird sanctuary) in Rajasthan and Pulicat Lake in Andhra Pradesh host thousands of ‘migratory birds’ coming from Siberia and other extremely cold northern regions.

(v) Suspend life activities :

In bacteria, fungi and lower plants, various kinds of thick-walled spores are formed which help them survive unfavoruable conditions. They germinate (come out of the spore wall and produce a normal active organisms) on the return of suitable environmental conditions.

Some animals can avoid the stress by escaping in ‘time’ (migration is – escaping in space’). The familiar case of ‘Polar bears’ going into hibernation during winter is an example of escape in time. Some snails and fish go into aestivation to avoid summer-related problems – heat and desiccation.

Diapause :

Certain organisms show delay in development, during periods of unfavourable environmental conditions and spend some period in a state of ‘inactiveness’ called ‘diapause’. This dormant period in animals is a mechanism to survive extremes of temperature, drought, etc. It is seen mostly in insects and embryos of some fish. Under unfavourable conditions many zooplankton species in lakes and ponds are known to enter diapause.

Question 2.

Write an essay on water as an ecological factor. (T.Q.)

Answer:

Water :

Water is another important factor influencing the life of organisms. Life is unsustainable without water. Its availability is so limited in deserts that only certain special adaptations make it possible for them to live there. You might think that organisms living in oceans, lakes and rivers should not face any water-related problems, but it is not true. For aquatic organisms the quality (chemical composition, pH, etc.,) of water becomes important.

The salt concentration is less than 5 percent in inland waters, and 30 – 35 percent in the seawater. Some organisms are tolerant to a wide range of salinities (euryhaline), but others arerestricted to a narrow range (stenohaline). Many freshwater animals cannot live for long in sea water and vice versa because of the osmotic problems, they would face.

Adaptations in freshwater habitat: Animals living in freshwaters have to tackle the problem of endosmosis. The osmotic pressure of freshwater is very low and that of the body fluids of freshwater organisms is much higher. So water tends to enter into bodies by endosmosis. To maintain the balance of water in the bodies, the freshwater organisms acquired several adaptation such as, contractile vacuoles in the freshwater protozoans, large glomerular kidneys in fishes, etc. They send out large quantities of urine, along which some salts are also lost.

To compensate the ‘salt loss’ through urine, freshwater fishes have ‘salt absorbing’ ‘chloride cells’ in their gills. The major problem in freshwater ponds is – in summer most of the ponds dry up. To overcome this problem most of the freshwater protists undergo encystment. The freshwater sponges produce asexual reproductive bodies, called gemmules, to tide over the unfavourable conditions of the summer. The ‘African lungfish’, Protopterus, burrows into the mud and forms a ‘gelatinous cocoon’ around it, to survive, in summer.

Adaptations in marine habitat :

Seawater is high in salt content compared to that of the body fluids. So, the marine animals continuously tend to lose water from their bodies by exosmosis and face the problem of dehydration. To overcome the problem of water loss, marine fishes have aglomerular kidneys with less number of nephrons. Such kidneys minimize the loss of water through urine. To compensate water loss the marine fish drink more water, and along with this water, salts are added to the body fluids and disturb the internal equilibrium.

To maintain salt balance (salt homeostasis) in the body, they have salt secreting chloride cells in their gills. Marine birds like sea gulls and penguins eliminate salts in the form of salty fluid that drips through their nostrils. In turtles the ducts of chloride secreting glands open near the eyes. Some cartilaginous fishes retain urea and trimethylamine oxide (TMO) in their blood to keep the body fluid isotonic to the sea water and avoid dehydration of the body due to exosmosis.

Water related adaptations in brackish water animals :

The animals of brackish water are adapted to withstand wide fluctuations in salinity. Such organisms are called euryhaline animals and those that can’t withstand are known as stenohaline. The migratory fishes such as salmon and Hilsa are anadromous fishes i.e., they migrate from the sea to freshwater, for breeding; Anguilla bengalensis is a catadromous fish i.e., it migrates from the river to sea, for breeding. In these fishes their glomerular kidneys are adjusted to changing salinities.

The chloride cells are adapted to excrete or absorb salts depending on the situation. On entering the river salmon drinks more freshwater to maintain the concentration of body fluids equal to that of the surround water.

Water related adaptations for terrestrial life :

In the absence of an external source of water, the kangaroo rat of the North American deserts is capable of meeting all its water requirements through oxidation of its internal fat (in which water is a by product – metabolic water). It also has the ability to concentrate its urine, so that minimal volume of water is lost in the process of removal of their excretory products.

Question 3.

Give an account of various types of interactions among the animal species of an ecosystem.

Answer:

Inter – specific Interactions :

Inter – specific interactions arise from the interaction of populations of two different species. They could be beneficial, detrimental or neutral (neither harmful nor beneficial) to one of the species or both. Assigning a V sign for beneficial interaction, sign for detrimental and ‘O’ for neutral interaction, let us look at all the possible outcomes of inter-specific interactions.

The interactions between species are grouped into four types. They are mutualism, commensalism, parasitism and amensalism. Both the species benefit in mutualism and both lose in competition in their interactions with each other. The interaction where one species is benefited and the other is neither benefited nor harmed is called commensalism. In amensalism on the other hand one species is harmed whereas the other is unaffected. In both parasitism and ‘predation’only one species benefits (parasite and predator, respectively) and the interaction is detrimental to the other species (host and prey, respectively). Predation, parasitism and commensalisms share a common characteristic – the interacting species live closely together.

Population Interactions – Types

| Name of Interaction | Species A | Species B |

| Mutualism | + | + |

| Competition | – | – |

| Predation | + | – |

| Parasitism | + | – |

| Commensalism | + | 0 |

| Amensalism | – | 0 |

Predation :

What would happen to all the energy fixed by autotrophic organisms if the community has no animals to eat the plants? We can think Of predation as nature’s way of transferring the energy fixed by plants to higher trophic levels. When we think of predator and prey, most probably it is the tiger and the deer that readily come to our mind, but a sparrow eating any seed is also a type of predator (a seed predator also called granivore). Although animals eating plants are categorized separately as herbivores, they are, in a broad ecological context, not very different from predators.

Besides acting as ‘conduits’ / ‘pipelines’ for energy transfer across trophic levels, predators play other important roles. They keep the prey populations under control. In the absence of predators, the prey species could achieve very high population densities and cause instability in the ecosystem. Predators have different types of functions to play in nature. They include :

A. Predator as a biological control :

The prickly pear cactus introduced into Australia in the early 1920s caused havoc by spreading rapidly into millions of hectares of rangeland (vast natural grass lands). Finally, the invasive cactus was brought under control only after a cactus feeding predator (a moth) was introduced into the country. Biological control methods adopted in agricultural pest control are based on the ability of the predators to regulate prey populations.

B. Predators maintain ‘species diversity’ :

Predators also help in maintaining species diversity in a community, by reducing the intensity of competition among competing prey species. In the rocky intertidal communities of the American Pacific Coast, the starfish Pisaster is an important predator. In a field experiemnt, when all the starfish were removed from an enclosed intertidal area, more than 10 species of invertebrates became extinct within a year, because of increased inter-specific competition.

C. Predators are prudent (practical) pertaining to preys :

If a predator is too efficient and overexploits its prey, then the prey might become extinct and following it, the predator will also become extinct due to lack of food. This is the reason why predators in nature are ‘prudent’.

Prey species have evolved various defenses to lessen the impact of predation they include :

a) Preys fool (deceive) or avoid their predators :

Some species of insects and frogs are cryptically – coloured (camouflaged) to avoid being detected easily by the predator. Some are poisonous and therefore avoided by the predators.

b) Preys defend by becoming distasteful to predators :

The Monarch butterfly is highly distasteful to its predator (bird) because of a special chemical present in its body. Interestingly, the butterfly acquires this chemical during its caterpillar stage by feeding on a poisonous weed.

c) Plants too have their defensive mechanisms :

For plants, herbivores are the predators. Nearly 25 percent of all insects are known to be phytophagous (feeding on plant sap and other parts of plants). The problem is particularly severe for plants because, unlike animals, they cannot escape from their predators. Plants therefore have evolved a variety of morphological and chemical defences against herbivores.

i) Thorns (Acacia, Cactus, etc.,) are the most common morphological means of defense. Many plants produce and store chemicals that make the herbivore sick when they are eaten, inhibit feeding or digestion, disrupt its reproduction or even kill it.

ii) We must have seen the weed Calotropis growing in abandoned fields. The plant produces highly poisonous cardiac glycosides and that is why we never see any cattle or goats browsing on this plant.

iii) A wide variety of chemical substances that we extract from plants on a commercial scale (nicotine, caffeine, quinine, strychnine, opium, etc.,) are produced by them actually as defences against grazers and browsers. Competition: When Darwin spoke of the struggle for existence and survival of the fittest in nature, he was convinced that interspecific competition is a ’potent force’ in the process of organic evolution, involving Nature Selection. It is generally believed that competition occurs when closely related species compete for the same resources that are limited, but this is not entirely true.

Parasitism :

Considering that the parasitic mode of life ensures free ‘lodging’ and ‘meals’, it is not surprising that parasitism has evolved in so many taxonomic groups from plants to higher vertebrates. Many parasites have evolved to be host-specific (they can parasitize only a specific species of host) in such a way that both host and the parasite tend to co-evolve; that is, if the host evolves special mechanisms for rejecting or resisting the parasite, the parasite has to evolve mechanisms to ‘counteract’ and ‘neutralize’ them, in order to continue successful parasitic relationship with the same host species. In order to leacl successful parasitic life, parasites evolved special adaptations, such as :

In order to lead successful parasitic life, parasites evolved special adaptations such as.

1.Loss of sense organs (which are not necessary for most parasites).

2.Presence of adhesive organs such as suckers, hooks tq cling on to the host’s body parts.

3.Loss of digestive system and presence of high reproductive capacity.

4.The life cycles of parasites are often complex, involving one or two intermediate hosts or vectors to facilitate parasitisation of their primary hosts.

e.g : 1: The human liver fluke depends on two intermediate (secondary ) hosts (a snail anda fish)to complete its life cycle.

e.g : 2 : The malaria parasite needs a vector (mosquito) to spread to otehr hosts. Majority of the parasites harm the host. They may reduce the survival, growth and reproduction of the host and reduce its population density. They might render the host more vulnerable to predation by making it physically weak.

Commmensalism :

This is the interaction in which one species benefits and the other is neither harmed nor benefited. Barnacles growing on the back of a whale benefit while the whale derives no noticeable benefit.

Mutualism :

This type of interaction benefits both the interacting species.

The most common examples of mutualism are found in plant-animal relationships. Plants need the help of animals for pollinating their flowers and dispersing their seeds. Animals obviously have to be paid ‘fees’ for the services that plants derive from them. Plants offer rewards in the form of pollen and nectar for pollinators and juicy and nutritious fruits for seed dispersing animals.

Question 4.

Describe lake as an ecosystem giving examples for the various zones and the biotic components in it. March 2015 – T.S ; March 2013

Answer:

Lake Ecosystem :

To understand the fundamentals of an aquatic ecosystem, let us take a ‘lake’ as an example. This is fairly a self-sustainable unit and rather a simple example that explains even the complex interactions that exist in an aquatic ecosystem.

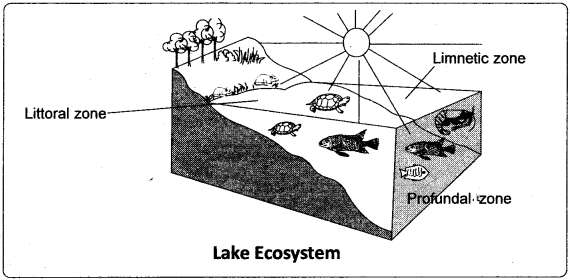

Lakes are large inland water bodies containing standing/still water (Recall: Lentic community). They are deeper than ponds (pond is not an ideal example as it is very shallow). Most lakes contain water throughout the year. In deep lakes, light cannot penetrate more than 200 meters, in depth. They are vertically stratified in relation to light intensity, temperature, pressure, etc. Deep water lakes contain three distinct zones namely, i) littoral zone, ii) limnetic zone, and iii) profundal zone.

Littoral zone :

It is the shallow part of the lake closer to the shore. Light penetrates up to the bottom. It is ‘euphoric’ (having good light), has rich vegetation and higher rate of photosynthesis, hence rich in oxygen.

Limnetic zone :

It is the open water zone away from the shore. It extends up to the effective light penetration level, vertically. The imaginary line that separates the limnetic zone from the profundal zone is known as zone of compensation/ compensation point / light compensation level. It is the zone of effective light penetration. Here the rate of photosynthesis is equal to the rate of respiration. Limnetic zone has no contact with the bottom of the lake.

Profundal zone :

It is the deep water area present below the limnetic zone and beyond the depth of effective light penetration. Light is absent. Photosynthetic organisms are absent and so the water is poor in oxygen content. It includes mostly the anaerobic organisms which feed on detritus.

The organisms living in lentic habitat are classified into pedonic forms, which live at the bottom of the lake and those living in the open waters of lakes, away from the shore vegetation are known as limnetic forms.

Biota (animal and plant life of a particular region) of the littoral zone :

Littoral zone is rich with pedonic flora (especially up to the depth of the effective light penetration.) At the shore proper emergent vegetation is a abundant with firmly fixed roots in the bottom of the lake and shoots and leaves are exposed above the level of water. These are amphibious plants. Certain emergent rooted plants of littoral zone are the cattails (Typha), bulrushes (Scirpus), arrowheads (Sagittaria). Slightly deeper are the rooted plants with floating leaves, such as the water lilies (Nymphaea), Nelumbo, Trapa, etc. Still deeper are the submerged plants such as Hydrilla, Chara, Potamogeton, etc. The free floating vegetation includes Pistia, Wolffia, Lemna (duckweed), Azolla, Eichhornia, etc.

The phytoplankton of the littoral zone composed of diatoms (Coscinodiscus, Nitzschia, etc.), green algae (Volvox, Spirogyra, etc.), euglenoids (Euglena, Phacus, etc.), and dinoflagellaes (Gymnodinium, Cystodinium, etc.)

Animals, the consumers of the littoral zone, are abundant in this zone of the lake. These are categorized into zooplankton, neuston, nekton, periphyton, and benthos. The zooplankton of the littoral zone consists of ‘water fleas’ such as Daphnia rotifers and ostracods.

The animals living at the air – water interface constitute the ‘neuston’. They are of two types, the epineuston and hyponeuston. Water striders (Gerris), beetles, water bugs (Dineutes) form the epineustone / supraneuston and the hyponeuston/ infraneuston includes the ‘larvae of mosquitoes’.

The animals such as fishes, amphibians, water snakes, terrapins, insects like ‘water scorpion’ (Ranatra), ‘back swimmer’ (Notonecta), ‘dividing beetles’ (Dytiscus), capable of swimming constitute the nekton.

The animals that are attached to / creeping on the aquatic plants such as the ‘water snails’, ‘nymphs of insects’, ‘bryozoans’, ‘turbellarians’, etc., constitute the ‘periphyton’.

The animals that rest on or move on the bottom of the lake constitute the ‘benthos’ e.g. red annelids, chironomid larvae, cray fishes, some isopods, amphipods, clams, etc.

Biota of the limnetic zone :

Limnetic zone is the largest zone of a lake. It is the region of rapid variations of the level of the water, temperature, oxygen availability, etc., from time to time. The limnetic zone has autotrophs (photosynthetic plants) in abundance. The chief autotrophs of this region are the phytoplankton such as the euglenoids, diatoms, cyanobacteria, dinoflagellates and green algae. The consumers of the limnetic zone are the zooplanktonic organisms such as the copepods. Fishes, frogs, water snakes, etc., form the limnetic nekton.

Biota of the profundal zone :

It includes the organisms such as decomposers (bacteria), chironomid larvae, Chaoborus (Phantom larva), red annelids, clams, etc., that are capable of living in low oxygen levels. The decomposers of this zone decompose the dead plants and animals and release nutrients which are used by the biotic communities of both littoral and limnetic zones.

The lake ecosystem performs all the functions of any ecosystem and of the biosphere as a whole, i.e., conversion of inorganic substances into organic material, with the help of the radiant solar energy by the autotrophs; consumption of the autotrophs by the heterotrophs; decomposition and mineralization of the dead matter to release them back for reuse by the autotrophs (recycling of minerals).

Question 5.

Give an account of the various types of ecosystems on the Earth.

Answer:

An ‘ecosystem’ is a functional unit of nature, where living organisms interact among themselves and also with the surrounding physical environment. Ecosystem varies greatly in size from a small pond to a large forest or a sea. Many ecologists regard the entire biosphere as a ‘global ecosystem’, as a composite of all local ecosystems on Earth. Since this system is too big and complex to be studied at one time, it is convenient to divide it into two basic categories, namely natural and artificial. The natural ecosystems include aquatic ecosystems of water and terrestrial ecosystems of the land. Both types of natural and artificial ecosystems have several subdivisions.

The Natural Ecosystems :

These are naturally occurring ecosystems and there is no role of humans in the formation of such types of ecosystems. These are categorized mainly into two types – aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems.

Aquatic Ecosystems :

Based on the salinity of water, three types of aquatic ecosystems are identified marine, freshwater, and estuarine.

i. The Marine Ecosystem :

It is the largest of all the aquatic ecosystems. It is the most stable ecosystems.

ii. Estuarine Ecosystem :

Estuary is the zone where river joins the sea. Sea water ascends up into the river twice a day (effect of high tides and low tides). The salinity of water in an estuary also depends on the seasons. During the rainy season out flow of river water makes the estuary less saline and the opposite occurs during the summer. Estuarine organisms are capable of withstanding the ‘fluctuations’ in salinity.

iii. The Freshwater Ecosystem :

The freshwater ecosystem is the smallest aquatic ecosystem. It includes rivers, lakes, ponds, etc. It is divided into two groups – the lentic and lotic. The still water bodies like ponds, lakes, reservoirs, etc., fall under the category of lentic ecosystems, whereas, streams, rivers and flowing water bodies are called lotic ecosystems. The communities of the above two types are called lentic and lotic communities respectively. The study of freshwater ecosystem is called as limnology.

The Terrestrial Ecosystems :

The ecosystems of land are known as terrestrial ecosystems. Some examples of terrestrial ecosystems are the forest, grassland and desert.

i. The forest Ecosystems :

The two important types of forests seen in India are i) tropical rain forest and ii) tropical deciduous forests.

ii. The Grassland Ecosystems :

These are present the Himalayan region in India. They occupy large areas of sandy and saline soils in Western Rajasthan.

iii. Desert Ecosystems :

The areas having less than 25 cm rainfall per year are called desert. They have characteristics flora and fauna. The deserts can be divided into two types – hot type and cold type deserts. Thar Desert in Rajasthan is the example for hot type of desert. Cold type desert is seen in Ladakh.

Artificial Ecosystems :

These are man-made ecosystems such as agricultural or agro-ecosystems. They include cropland ecosystems, aquaculture ponds and aquaria.

Question 6.

Describe different types of food chains that exist in an ecosystem. March 2019, May 2017 – A.P.; May/June, Mar. 2014

Answer:

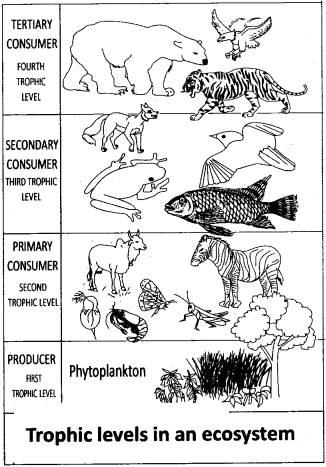

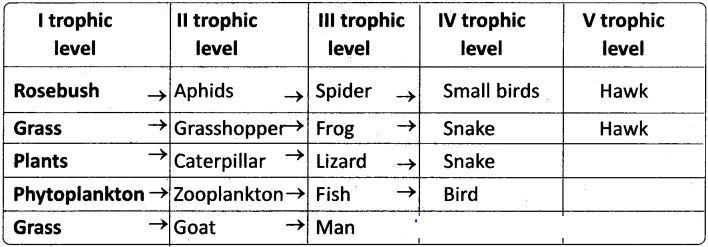

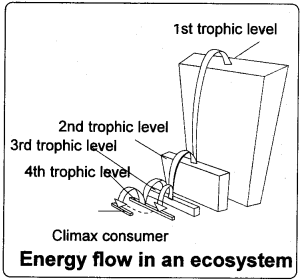

Energy flows into biological systems (ecosystems) from the Sun. The biological systems of environment include several food levels called trophic levels. A trophic level is composed of those organisms which have the same source of energy and having the same number of steps away from the sun. Thus a plant’s trophic level is one, while that of a herbivore – two, and that of the first level carnivore – three. The second and third levels of the carnivores occupy fourth and fifth trophic levels respectively.

A given organism may occupy more than one trophic level simultaneously. One must remember that the trophic level represents a functional level. A given species may occupy more than one trophic level in the same ecosystem at the same time; for example, a sparrow is a primary consumer when it eats seeds, fruits, and a secondary consumer when it eats insects and worms.

The food energy passes from one trophic level to another trophic level mostly from the lower to higher trophic leves. When the ‘path of food energy is ‘linear’, the components resemble the ‘links’ of a chain, and it is called ‘food chain’. Generally a food chain ends with decomposers. The three major types of food chains in an ecosystem are Grazing Food Ghain, Parasitic Food Chain and Detritus Food Chain.

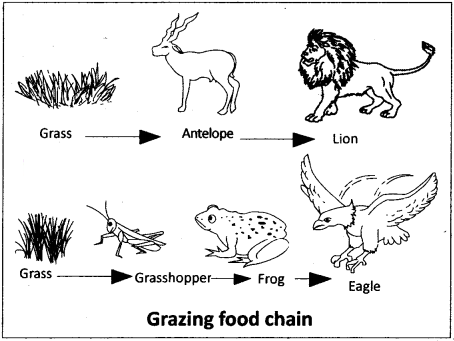

I.Grazing Food Chain (GFC) :

It is also known as predatory food chain. It begins with the green plants (producers) and the second, third and fourth trophic levels are occupied by the herbivores, primary carnivores and secondary carnivores respectively. In some food chains there is yet another trophic level – the climax carnivores. The number of trophic levels in food chains varies from 3 to 5 generally. Some examples for grazing food chain (GFC) are given below.

II. Parasitic food chain :

Some authors included the ‘parasitic Food Chains’ as a part of the GFC. As in the case of GFCs, it also begins with the producers, the plants (directly or indirectly). However, the food energy passes from large organisms to small organisms in the parasitic chains. For instance, a tree which occupies the 1st trophic level provides shelter and food for many birds. These birds host many ecto-parasites and endo-parasites. Thus, unlike in the predator food chain, the path of the flow of energy includes fewer, large sized organisms in the lower trophic levels, and numerous, small sized organisms in the successive higher trophic levels.

III. Detritus Food Chain :

The detritus food chain (DFC) begins with dead organic matter (such as leaf litter, bodies of dead organisms). It is made up of Decomposers which are heterotrophic organisms, mainly the ‘fungi’ and ‘bacteria’. They meet their energy and nutrient requirements by degrading dead organic matter or detritus. These are also known as saprotrophs (sapro : to decompose)

Decomposers secrete digestive enzyme that breakdown dead and waste materials (such as faeces) into simple absorbable substances. Some examples of detritus food chains are :

1.Detritus (formed from leaf litter) – Earthworms – Frogs – Snakes.

Dead animals – Flies and maggots – Frogs – Snakes.

In an aquatic ecosystem, GFC is the major ‘conduit’ for the energy flow. As against this, in a terrestrial ecosystem, a much larger fraction of energy flows through the detritus food chain than through the GFC. Detritus food chain may be connected with the grazing food chain at some levels. Some of the organisms of DFC may form the prey of the GFC animals. For example, in the detritus food chain given above, the earthworms of the DFC may become the food of the birds of the GFC. It is to be understood that food chains are not ‘isolated’ always.

Question 7.

Write an essay on productivity of an ecosystem.

Answer:

The rate of production of biomass is called productivity. It can be divided into primary and secondary productivities.

I. Primary productivity is defined as the amount of biomass or organic matter produced per unit area over a period of time by plants, during photosynthesis. It can be divided into gross primary productivity (GPP) and net primary productivity (NPP).

a) Gross primary productivity of an ecosystem is the rate of production of organic matter during photosynthesis. A considerable amount of GPP is utilized by plants for their catabolic process (respiration).

b) Net primary productivity Gross primary productivity minus respiratory loss (R), is the net primary productivity (NPP). On average about 20 – 25 percent of GPP is used for the catabolic (respiratory) activity.

GPP – R = NPP

The net primary productivity is the biomass available for the consumption of the heterotrophs (herbivores and decomposers).

II. Secondary productivity is defined as the rate of formation of new organic matter by consumers.

Question 8.

Give an account of flow of energy in an ecosystem. March 2015 – A.P.

Answer:

Energy Flow :

Except for the deep sea hydro-thermal ecosystem, sun is the only source of energy for all ecosystems on Earth. Of the incident solar radiation less than 50 per cent of it is photosynthetically active radiation (PAR). We know that plants and photosynthetic bacteria (autotrophs), fix Sun’s radiant energy to synthesise food from simple inorganic materials. Plants capture only 2-10 percent of the PAR and this small amount of energy sustains the entire living world. So, it is very important to know how the solar energy captured by plants flows through different organisms of an ecosystem.

All heterotrophs are dependent on the producers for their food, either directly or indirectly. The law of conservation of energy is the first law of thermodynamics. It states that energy may transform from one form into another form, but it is neither created nor destroyed. The energy that reaches earth is balanced by the energy that leaves the surface of the earth as invisible heart radiation.

The energy transfers in an ecosystem are essential for sustaining life. Without energy transfers there could be no life and ecosystems. Living beings are the natural proliferations that depend on the continuous inflow of concentrated energy.

Further, ecosystems are not exempted from the Second Law of thermodynamics. It states that no process involving energy transformation will spontaneously occur unless there is degradation of energy. As per the second law of thermodynamics – the energy dispersed is in the form of unavailable heat energy, and constitutes the entropy (energy lost or not available for work in a system). The organisms need a constant supply of energy to synthesize the molecules they require. The transfer of energy through a food chain is known as energy flow.

A constant input of mostly solar energy is the basic requirement for any ecosystem to function. The important point to note is that the amount of energy available decreases at successive trophic levels. When an organism dies, it is converted to detritus or dead biomass that serves as a source of energy for the decomposers. Organisms at each trophic level depend on those at the lower trophic level, for their energy demands.

Each trophic level has a certain mass of living material at a particular time, and it is called the standing crop. The standing crop is measured as the mass of living organisms (biomass) or the number of organisms per unit area. The biomass of a species is expressed in terms of fresh or dry weight (dry weight is more accurate because water contains no usable energy).

The 10 percent Law :

The 10 percent law for the transfer of energy from one trophic level to the next was introduced by Lindeman (the Founder of the modern Ecosystem Ecology).

According to this law, during the transfer of energy from one trophic level to the next, only about 10 percent of the energy is stored / converted as body mass / biomass. The remaining is lost during the transfer or broken down in catabolic activities (Respiration).

Lindeman’s rule of trophic efficiency /Gross ecological efficiency is one of the earliest and most widely used measures of ecological efficiency. For example, if the NPP (Net primary production) in a plant is 100 kJ, the organic substance converted into body mass of the herbivores which feeds on it is 10 kJ only. Similarly the body mass of the carnivore -1 is 1 kJ only.

Question 9.

List out the major air pollutants and describe their effects on human beings. March 2018, 17 – A.P.

Answer:

The major air pollutants :

- Carbon monoxide (CO) :

It is produced mainly due to incomplete combustion of fossil fuels. Automobiles are a major cause of CO pollution in larger cities and towns. Automobile exhausts, fumes from factories, emissions from power plants, forest fires and even burning of fire-wood contribute to CO pollution. Haemoglobin has greater affinity for CO and so CO competitively interferes with oxygen transport. Co causes symptoms such as headache and blurred vision at lower concentrations. In higher concentrations, it leads to coma and death. - Carbon Dioxide (CO2) :

Carbon dioxide is the main pollutant that is leading to global warming. Plants utilize CO2 for photosynthesis and all living organisms emit carbon dioxide in the process of respiration. With rapid urbanization, automobiles, aeroplanes, power plants, and other human activities that involve the burning of fossil fuels such as gasoline, carbon dioxide is turning out to be an important pollutant of concern. - Sulphur Dioxide (SO2) :

It is mainly produced by burning of fossil fuels. Melting of sulphur ores is another important source for SO2 pollution. Metal smelting and other industrial processes also contribute to SO2 pollution. Sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides are the major causes of acid rains, which cause acidification of soils, lakes and streams, and also accelerated corrosion of buildings and monuments. High concentrations of sulphur dioxide (SO2) can result in breathing problems in asthmatic children and adults. Other effects associated with long – term exposure to sulphur dioxide, include respiratory illness, alterations in the lungs’ defenses and aggravation of existing cardiovascular problems.

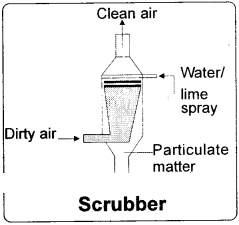

To control SO2 pollution, the emissions are filtered through scrubbers. Scrubbers are devices that are used to clean the impurities in exhaust gases. Gaseous pollutants such as SO2 are removed by scrubbers.

- Nitrogen Oxides :

Nitrogen oxides are considered to to be major primary pollutants. The source is mainly automobile exhaust. The air polluted by nitrogen oxides is not only harmful to humans and animals, but also dangerous for the life of plants. Nitrogen oxide pollution also results in acid rains and formation of photochemical smog. The effect of nitrogen oxides on plants include the occurrence of necrotic spots on the surface of leaves. Photosynthesis is affected in crop plants and they yield is reduced. Nitrogen oxides combine with volatile organic compounds by the action of sunlight to form secondary pollutants called Peroxyacetyl nitrate (PAN) which are found especially in photochemical smog. They are powerful irritants to eyes and respiratory tract. - Particulate matter/Aerosols :

Tiny particles of solid matter suspended in a gas or liquid constitute the ‘particulate matter’. ‘Aerosols’ refer to particles and / or liquid droplets and the gas together (a system of colloidal particles dispersed in a gas). Combustion of ‘fossil fuels’ (petrol, diesel, etc.,), fly ash produced in thermal plants, forest fires, cement factories, asbestos mining and manufacturing units, spinning and ginning mills etc., are the main sources of particulate matter pollution. According to the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) particles of 2.5 micrometers or less in diameter are highly harmful to man and other air breathing organisms.

Question 10.

What are the causes of water pollution and suggest measures for control of water pollution?

Answer:

Inferior quality of water, caused by pollution of natural waters is a major problem world is facing today. It is posing all the rivers in India are grossly polluted either by sewage or discharge of industrial effluents.

The major water pollutants :

Domestic Sewage :

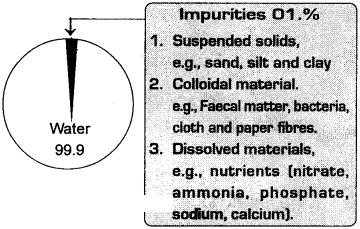

Sewage is the major source of water pollution in large cities and towns. It mainly consists of human and animal excreta and other waste materials. It is usually released into freshwater bodies or sea directly. As per the regulations the sewage has to be passed through treatment plants before it is released into the water courses. Only 0.1 percent of impurities from domestic sewage are making these water sources unfit for human consumption. In the treatment of sewage, solids are easy to remove. Removal of dissolved salts such as nitrates, phosphates and other nutrients and toxic metal ions and organic compounds is much more difficult. Domestic sewage primarily contains biodegradable organic matter, which will be readily decomposed by the action of bacteria and other microorganisms.

Effect of sewage discharge on some important characteristics of a river

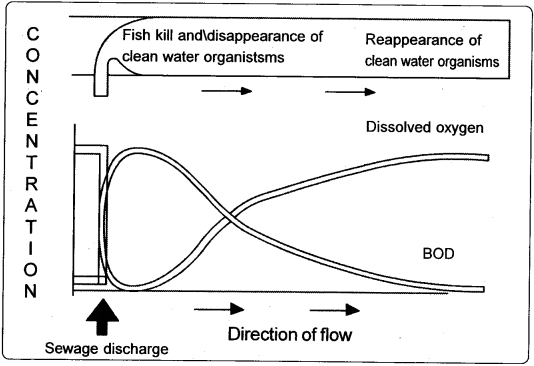

Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD) :

BOD is measure of the content of biologically degradable substances in sewage. The organic degradable substances are broken-down by microorganisms using oxygen. The demand of oxygen is measured in terms of the oxygen consumed by microorganisms over a period of 5 days (BOD 5) or seven days (BOD 7). BOD forms an index for measuring pollution load in the sewage. Microorganisms involved in biodegradation of organic matter in water bodies consume a lot of oxygen, and as a result there is a sharp decline in dissolved oxygen causing death offish and other aquatic animals.

Algal blooms :

Presence of large amounts of nutrients in waters also causes excessive growth of planktonic algae and the phenomenon is commonly called ‘algal blooms’. Algal blooms impart distinct colour to the water bodies and deteriorate the quality of water. It also causes mortality of fish. Some algae which are involved in algal blooms are toxic to human beings and animals.

Excessive growth of aquatic plants such as the common water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), the world’s most problematic aquatic weed which is also called ‘Terror of Bengal’ causes blocks in our water ways. They grow faster than our ability to remove them. They grow abundantly in eutrophic water bodies (water bodies rich in nutrients) and lead to imbalance in the ecosystem dynamics of the water body.

Sewage arising from homes and hospitals may contain undesirable pathogenic microorganisms. If it is released untreated into water resources, there is a likelihood of outbreak of serious diseases, such as dysentery, typhoid, jaundice, cholera etc.

Industrial Effluents :

Untreated industrial effluents released into water bodies pollute most of the rivers, fresh water streams, etc. Effluents contain a wide variety of both inorganic and organic pollutants such as oils, greases, plastics, metallic wastes, suspended solids and toxins. Most of them are non-degradable. Arsenic, Cadmium, Copper, Chromium, Mercury, Zinc, and Nickel are the common heavy metals discharged from industries.

Effects :

Organic substances present in the water deplete the dissolved oxygen content in water by increasing the BOD (Biological oxygen demand) and COD (Chemical oxygen demand). Most of the inorganic substances render the water unfit for drinking. Outbreaks of dysentery, typhoid, jaundice, cholera etc., are caused by sewage pollution.

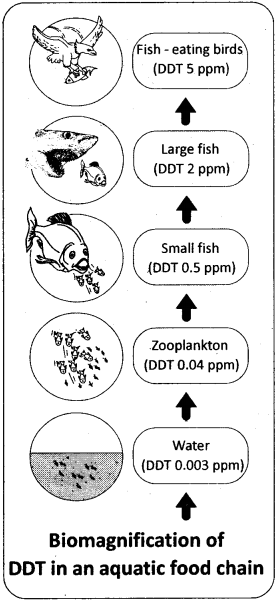

b) Biomagnification :

Increase in the concentration of the pollutant or toxicant at successive trophic levels in an aquatic food chain is called Biological Magnification or Bio – magnification. This happens in the instances where a toxic substance accumulated by an organism is not metabolized or excreted and thus passes on to the next higher trophic level. This phenomenon is well known regarding DDT and mercury pollution.

As shown in the above example, the concentration of DDT is increased at successive trophic levels starting at a very low concentration of 0.003 ppb (ppb – parts per billion) in water, which ultimately reached an alarmingly high concentration of 25 ppm (ppm – parts per million) in fish-eating birds, through bio-magnification. High concentrations of DDT disturb calcium metabolism in birds, which causes thinning of egg shell and their premature breaking, eventually causing decline in bird populations.

Eutrophication :

Natural ageing of a lake by nutrient enrichment of its water is known as eutrophication. In a young lake, the water is cold and clear, supporting little life. Gradually nutrients such as nitrates and phosphates are carried into the lake via streams, in course of time. This encourages the growth of aquatic algae and other plants. Consequently the animal life proliferates, and organic matter gets deposited on the bottom of the lake. Over centuries, as silt and organic debris piles up, the lake grows shallower and warmer. As a result, the aquatic organisms thriving in the cold environment are gradually replaced by warm-water organisms. Marsh plants appear by taking root in the shallow regions of the lake. Eventually, the lake gives way to large masses of floating plants (bog) and finally converted into land.

Depending upon the climatic conditions, size of the lake and other factors, the natural ageing of a lake may span thousands of years. However, pollutants from human ativity (anthropogenic) radically accelerate the aging process. This phenomenon is called ‘Cultural or Accelerated eutrophication’.

During the past century, lakes in many parts of the earth have been severey eutrophied by sewage, agricultural and industrial wastes. The prime contaminants are nitrates and phosphates, which are the ’chief plant nutrients’. The dissolved oxygen which is vital to other aquatic clife is depleted. At the same time, other pollutants flowing into the lake may poison the whole population of fish, whose decomposing remains further deplete the dissolved oxygen content in the water.

Thermal pollution :

Water is used as a coolant in Thermal power plants and other industries. Hot water flowing out of industries also constitute an important category of pollutants. Thermal waste water eliminates sensitive organisms (Stenothermal organisms such as fish – especially the juveniles) downstream and may enhance the growth of plants and fish in extremely cold areas but, only after causing damage to the indigenous flora and fauna.

Ecological Sanitation – ’Ecosan Toilets’ :

Generally it is assumed that removal of wastes requires water, which means creation of sewage. If water is not used to dispose off human waste like excreta, and if one didn’t have to flush the tiolet after its use, a large amount of water can be saved. This is already a reality. Ecological sanitation is a substainable system for handling human excreta, using ‘dry composting toilets’. This is a practical, hygienic, efficient and cost-effective solution to human waste disposal. The key point to note here is that, with this composting method, human excreta can be recycled into a resource (as natural fertiliser), which reduces the need for chemical fertilizers. ‘EcoSan’ toilets are in use in many parts of Kerala and Sri Lanka.

Question 11.

Write an essay on soil pollution and measures to control soil pollution.

Answer:

Solid Wastes :

Any thing (substance/ material / articles / goods) that is thrown out as waste in solid form is referred to as solid waste. Municipal solid wastes are wastes from homes, offices, institutions, shops, hotels, restaurants etc., in towns and cities.

The municipal solid wastes generally consist of paper, food wastes, plastics, glass, metals, rubber, leather, textile, etc. The wastes are burnt to reduce the volume of the wastes. But generally wastes are not completely burnt and left as open dumps which often serve as the breeding grounds for rats and flies. As the substitute for open-burning dumps, sanitary landfills are adopted. In a sanitary landfill, wastes are dumped in a depression or trench after compaction, and covered landfill, wastes are dumped in a depression or trench after compaction, and covered with dirt everyday. These is a danger of seepage of chemicals and pollutants from these landfills, which may contaminate the underground water resources.

The best solution is to develop awareness in the society on these environmental issues. All wastes that we generate can be categorized into three types (a) biodegradable, (b) recyclable and (c) non-biodegradable. It is important that all garbage generated should be sorted out category wise. The reusable or recyclable material has to be separated out and utilised. (Rag-pickers in the streets are doing a great job of separation of materials for recycling.) The biodegradable materials can be put into deep pits in the ground and be left for natural breakdown. The remaining non-biodegradable waste left over is to be disposed off properly.

The prime goal should be to reduce our garbage generation. But we are increasing the use of non-biodegradable products. We are packaging products of our daily use such as milk and water also in polythene bags. In cities and towns, many purchased things are packed in polystyrene and plastic packets. Thus we are contributing heavily to environmental pollution. State Governments across the country are trying to educate people on the reduction in use of plastic and use of eco-friendly packaging. We can do our bit by using carry-bags made of cloth or other natural fibres when we go for shopping and by refusing polythene bags.

i) Hospital wastes :

Hospitals generate hazardous wastes that contain disinfectants, harmful chemicals and also pathogenic micro-organisms. Such wastes also require careful treatment and disposal. The use of incinerators (to burn wastes) is essential for disposal of hospital waste.

ii) Electronic wastes (e-wastes) :

Irreparable computers and other electronic goods constitute the modern day pollutants called electronic wastes (e-wastes), e – wastes are buried in landfills or incinerated. Over half of the e-wastes generated in the developed world are exported to developing countries, mainly to China, India and Pakistan, where metals like copper, iron, silicon, nickel and gold are recovered during recycling process.

Unlike developed countries, which have specifically built facilities for recycling of e-wastes, recycling in developing countries often involves manual participation thus exposing workers to toxic substances present in e – wastes. Eventually recycling is the only solution for the treatment of e – wastes provided it is carried out in an environmental friendly manner.

iii) Agro – chemicals and their effects :

In the wake of the Green Revoltuion, use of inorganic fertilisers and pesticides has increased many times, for enhancing crop production. Pesticides, herbicides, fungicides, etc., are being increasingly used. They are also toxic to non-target organisms such as earthworms, nitrogen fixing bacteria, etc., that are important components of soil eco-system. Moreover due to bio-magnification, the harmful chemicals pose a great threat to human health. Indiscriminate use of fertilizers will lead to increased drain of nutrients into the nearby aquatic ecosystems causing eutrophication and the consequent effects.

iv) Radioactive wastes :

Initially, nuclear energy was hailed as a non-polluting way for generating electricity. Later on, it was realised that the use of nuclear energy has two very serious inherent problems. The first is accidental leakages, as occurred in the Three Mile Island (USA) and Chernobyl (Russia) and the second is the safe disposal of radioactive wastes.

Radiation, that is released from nuclear waste is extremely dangerous to biological organisms, because it induces mutations. Exposure to high doses of nuclear radiation is lethal as it can lead to cancers (e.g. leukemia). Therefore, nuclear waste is an extremely potent pollutant and has to be dealt with utmost caution. Storage of nuclear wastes should be done in suitably shielded containers and buried deep in the soil or oceans (about 500 meters). Even when done so, geological upheavals can bring them up, some day and cause radiation.